Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story stated that land above the Oso landslide zone was logged in 2005. The site was logged in 2004 and replanted in 2005.

The forester who clear-cut land above the Oso, Wash., landslide zone in 2004 says he followed standard procedures and state regulations when logging there.

Washington's Forest Practices Act restricts cutting in areas where loss of tree cover could lead to more groundwater flowing beneath and lubricating a landslide zone.

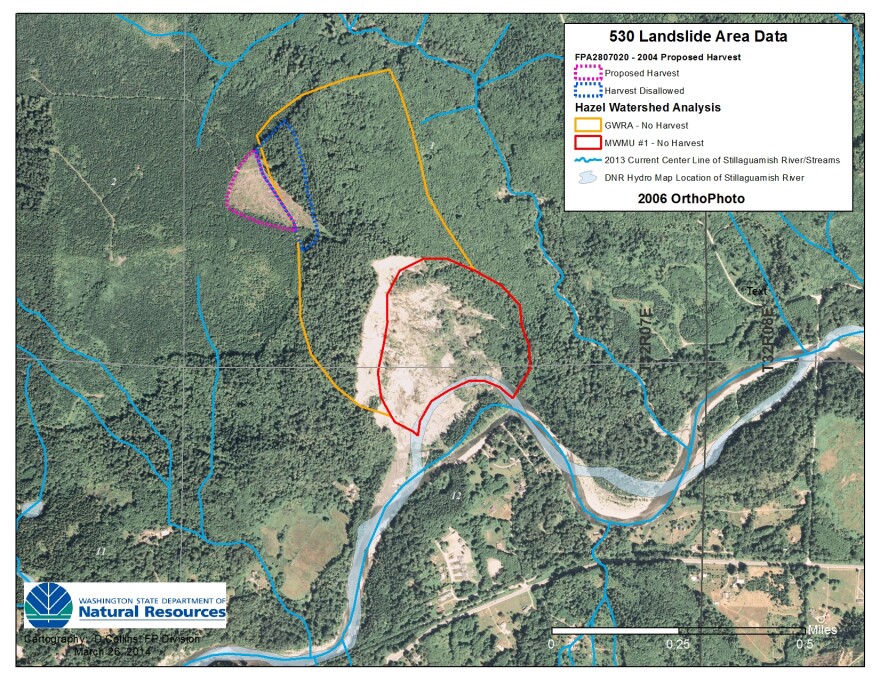

What role, if any, logging played in the catastrophic slide that killed more than 30 people in Oso on March 22 is unclear. Geologists say determining the causes of the slide will take detailed study. Aerial photos show a high cliff left behind by the landslide just touching the point of a pizza-slice-shaped clear-cut.

Ken Osborn spoke with reporters late last week for the first time since the catastrophic slide. He runs a small business called Arbor-Pacific Forestry in Mt. Vernon.

“Arbor-Pacific is essentially me and a bookkeeper, so not a sprawling operation,” Osborn said.

Arbor-Pacific manages 20,000 acres of private forest land in Skagit and Snohomish counties for its main client, another Mt. Vernon-based company called Grandy Lake Forest Associates. Osborn declined to identify the owners of Grandy Lake, but company filings indicate it is owned by Eberhard Gemmingen, Albrecht Gemmingen and Wolf-Eckart Gemmingen of Bavaria, Germany. They also own timber land in Germany and thousands of acres of pine and eucalyptus plantations in New Zealand.

[asset-pullquotes[{"quote": "If we muck around with [DNR] and try to get cute by pushing lines here and there, that will come back to haunt us.", "style": "inset"}]]Osborn has been managing Washington forest lands for the two companies for 27 years. He said when he heard about the Oso slide, he cut short his business trip to New Zealand.

"The little valley that got hammered, I go past that all the time," he said of the Oso area. "It was pretty painful for us all."

The day after returning from New Zealand, he headed to Oso. “A lot of the slide itself is on our property,” he said.

Osborn said much of the company's timber land on a plateau above the slide looked unaffected, but he wasn't able to get too close to the newly formed cliff atop the slide.

"We didn't look over the edge into the massive slide disaster area," he said. "It wasn't a safe place to be."

The Oso site has a well-documented history of landslides that have rendered much of the land unfit for timber or other uses. Trees grow crookedly there: They keep aiming for the sky despite their trunks' being moved around by the oozing, shifting ground. One scientist who has studied the site called them "crazy trees."

[asset-images[{"caption": "WSDOT photo of Oso slide area annotated by retired fisheries biologist Bill McMillan of Concrete, Wash.", "fid": "21519", "style": "card_280", "uri": "public://201403/WSDOT-McMillan.jpg", "attribution": "Credit Courtesy of WSDOT / Bill McMillan"}]]Walking The Line

Logging around deep landslide zones is essentially prohibited in Washington state. Legally, any areas that could funnel extra groundwater deep beneath the Oso landslide zone are supposed to be off limits, barring a detailed geotechnical study that timber companies rarely do. Groundwater lubricates deep landslides, and removing trees can increase the amount of rainwater that finds its way underground.

Osborn said he recognizes the connections between logging, groundwater and landslides. But he said the small, 7-acre clear-cut he oversaw in 2004 was carefully designed to stay out of the no-cutting area so it wouldn't worsen the risk of a landslide.

"I feel we did our job and complied with all the rules and regulations," Osborn said.

When planning that timber harvest, he brought in Seattle geologist Dan Miller and environmental manager Pat Stevenson with the Stillaguamish Tribe to help. The three walked the site and used yellow ribbons to mark the cut's boundary with the no-cutting zone designated by the Washington Department of Natural Resources.

Osborn said the perfectly straight lines of the DNR maps have to be ground-truthed in the field. "They're guidelines. They're initial steps because there are very few straight lines in nature," he said. "We have to make sure that we have it correct in the field."

Based on aerial photos of the Oso clear-cut, the DNR said in March that the cut appeared to stray into the no-cutting zone above the slide.

Osborn said it would have been stupid to try to log beyond the lines drawn by the DNR. "Building faith and trust with DNR is huge with us because they're the regulatory agency," he said. "If we muck around with them and try to get cute by pushing lines here and there, that will come back to haunt us."

Osborn, who has forestry degrees from the University of Washington and Yale, called the landslide a "dreadful natural disaster."

"If you have 100 percent saturated soils and you've got this incredibly powerful river banging away at the toe of the slope, nothing's going to stop it," he said.

Drag the map down to see the pizza-slice-shaped clear-cut at the top of the March 22 Oso landslide. Credit: Produced by Esri with imagery from the Washington State Department of Transportation.

Holding Back A River

DNR officials have also emphasized the area's unstable soils, heavy rain and undercutting by the North Fork Stillaguamish River as causes of the deadly slide.

So far this year, Darrington, just east of the Oso slide, has received 42 inches of rain. According to the National Weather Service, that's about 50 percent above normal for the first three months of the year.

After a destructive slide in 2006, the Stillaguamish Tribe installed a logjam at the base of the slide to prevent further erosion from below by the river.

That engineered logjam was still in place the week of the landslide, according to architect Davis Hargrave of Kirkland. "I saw it about a week and a half ago," he said last week.

Hargrave often spent weekends at his vacation home on Steelhead Drive before it was destroyed in the latest slide. He happened not to be there the Saturday that the neighborhood was swallowed by mud.

Hargrave said the engineered logjam looked like a stack of giant Lincoln Logs, held together by 1-inch steel cable. It was tall enough that he recalled teenagers diving off it into the river in warmer months, like a 3-meter diving board.

"It had suffered some damage," he said. "If somebody asked if it was working, I’d say yes."

Old Science

The DNR approved that 2004 timber sale right on the edge of what it defined as the sensitive zone, but the agency relied on a study from 1988, instead of the best available science. A 1997 geological study of the watershed led by Dan Miller showed much of the planned clear-cut would be inside the groundwater sensitive zone.

Miller said he just learned last month that the state had not incorporated his work into the protected area set up around the landslide-prone slope.

"This is a sad turn of events," Miller said of the his study not being put to use. "I believe the land managers did their best to follow the rules and do the right thing."

Miller said he thought it unlikely that a 7-acre clear-cut would have a large influence on a landslide that covered hundreds of acres.

Washington Lands Commissioner Peter Goldmark, who heads the DNR, called any suggestion that logging played a contributing role “disappointing” and said DNR has no plans for a moratorium on logging in areas similar to where the Oso slide happened.