On a recent morning at George T. Daniel Elementary School in Kent, the school bell had already rung. In the driveway, one minivan after another pulled up, spilling tardy students onto the sidewalk.

There are so many late students on this school – often dozens in a single day – that the main office can't contain them all. Now the office staff check in tardy students in the building's foyer.

"I was sleeping," one child explained.

"The volume was down on my alarm clock," another said.

Many other kids won’t show up at all today. Principal Patty Drobny said it’s usually the same kids who are late or absent.

Chronic absenteeism is a key predictor that kids won’t learn to read on time – and eventually won’t graduate. New data from the state schools office shows that one in six Washington students were chronically absent last year. That means they missed at least 18 days of the school year – or 10 percent.

Drobny said there are many reasons kids don’t make it to school. Sometimes cultural factors are at play.

"What I heard the other day [from a parent] was, ‘That’s my baby, I don’t want to force her up.’ And then we had a talk about ‘If it’s your baby and you care about her, that’s all the more reason to force her to get up in the morning,'" Drobny said.

Some immigrant families come from countries that are more relaxed about time. Many families rely on their children to babysit younger family members. Poverty can lead to everything from transportation problems to health issues for kids or their family members. Some students might stay home because they don’t feel safe or comfortable in school.

Discipline can skew the data, because out-of-school suspension also counts as an absence.

Hedy Chang, the executive director or Attendance Works, said that while chronic absence of course means that kids miss lessons, it predicts trouble in school for other reasons, too.

"Part of the reason why you want to track chronic absence is it’s an early indicator that there are other life issues that might also be affecting their academic performance," Chang said. Her organization advises Washington state on reducing absenteeism.

To get to the heart of the problem, some schools have gone beyond robocalls and form letters home when students are frequently late or absent. At Daniel Elementary, Principal Drobny meets with parents to figure out what’s getting in the way of school. She said parents are often startled when she tells them that even missing two days a month adds up to 10 percent of the school year.

Parents tend not to realize how much learning kids miss out on when they’re not in school, Drobny said – especially in kindergarten and first grade, which parents often consider optional.

"A lot of parents are surprised when they see what kids have to do. There’s that surprise factor of – 'Wow, when I was in kindergarten, we got to take naps!'" Drobny said.

When parents blame oversleeping, Drobny offers to give them an alarm clock from her stash in the office.

She’s only had one taker.

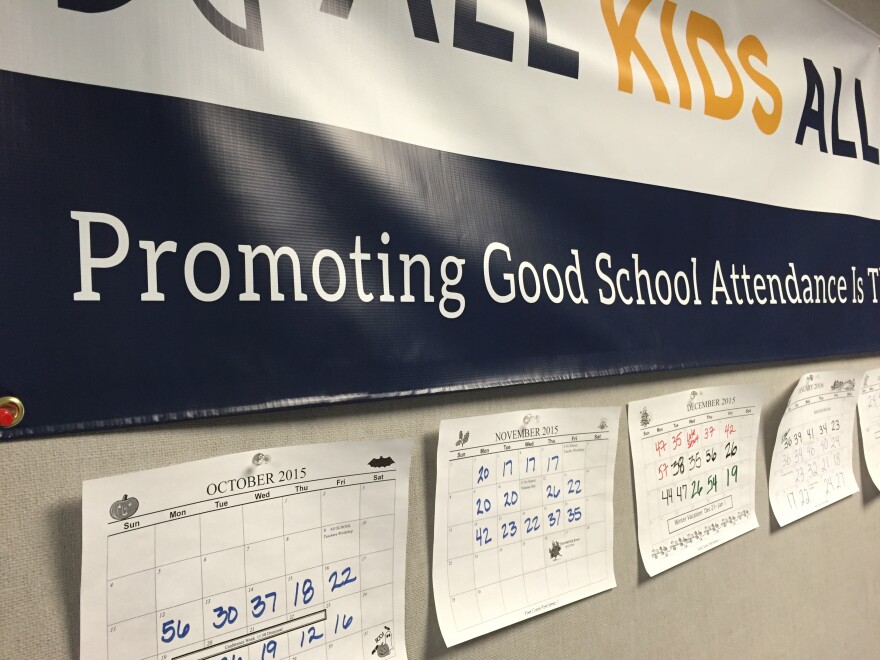

Drobny has stretched a giant chart across one hallway at the school to draw attention to the number of students who were tardy each day this school year. She’s promised students a big party if they are able to get the schoolwide tardy count down to the single digits. She’s just asking for one day.

At the state level, there’s a new initiative to educate parents, entice students and break down barriers to attendance. One possible strategy comes from New York City, where schools assign chronically absent students “success mentors.” That’s someone who keeps track of students’ attendance, acts like a cheerleader and helps students strategize if they’re having a hard time making it to school.

Chang said now that Washington state has released its chronic absenteeism data for the first time, districts will be able to see how they compare.

"It allows you to identify what we call a positive outlier, or a bright spot, that has characteristics that would suggest that they’d have a high level of chronic absence, but they actually are doing a great job,” Chang said.

The hope is that those “bright spot” districts can teach their peers how they get kids to come to school – ideally, on time.